If there's one thing I'm a casual nerd about, it's typography. I'm aggressively literate and spend most of my time reading and writing. When I read, I prefer a well-crafted page where the words flow smoothly and comprehending the message is not a tiresome task.

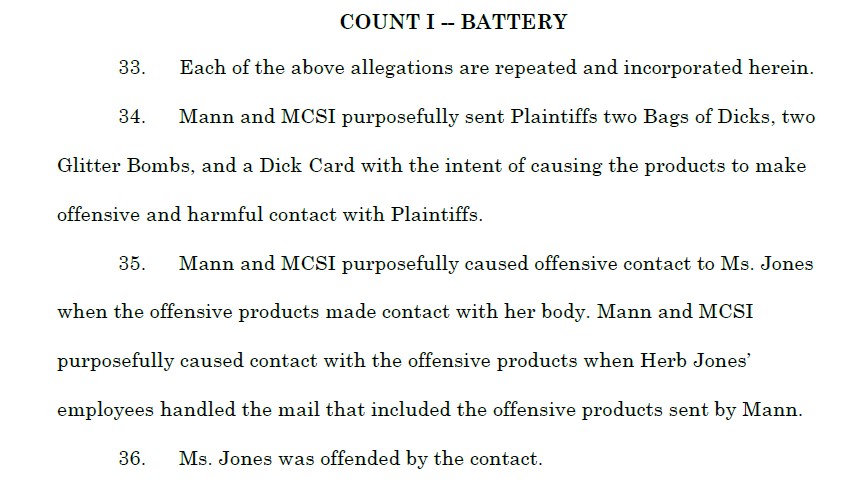

Lawyers are notorious for their clunky, cumbersome writing. "Legalese" and unnecessary string citations can obfuscate an otherwise strong argument, and can bore (or worse, confuse) the reader. But lawyers aren't just bad when it comes to content. They're also bad when it comes to format. Legal writing typically appears in the following form:

- 8.5 x 11 paper with 1 inch margins on all sides

- 12-14 point Times New Roman or Courier New

- Text simultaneously bold, italicized, and underlined for emphasis

- Left justification

- Confusing hierarchical headings (I. A. i. 1.)

This is fine, as a minimum standard. As long as you write in a language that the reader understands (some of us are actually fluent in legalese), you're at least doing okay.

But typical legal writing could be much, much better. It could actually take the reader's needs into consideration and be organized and presented in a way that assists understanding rather than frustrates it. Unfortunately, most lawyers do not care about this or actively work against any kind of change.

Matthew Butterick is not one of those lawyers. In fact, he's carved out a niche as the lawyer fighting against crappy aesthetics in legal writing. In 2010, the first version of his book Typography for Lawyers was released upon the world. It was well-received, and rightly so. It provided, in a clear and attractive way, useful advice on type composition (punctuation, symbols, signatures, hyphens, line breaks), text formatting, page composition, and fonts (my personal favorite topic).

It wasn't until I read Butterick's book that I started caring a lot about how my court pleadings and correspondence look. Upon his advice, I use bigger margins. I try, whenever possible, to use numerical headings with decimals rather than alternating letters and numbers. I also use better fonts than Times New Roman when I write motions, briefs, and letters. For motions and briefs, I use a font called Eldorado that looks classically bookish and highly readable. For letters, I use the ever-awesome Sabon, which is probably the greatest font ever (sorry, Helvetica). Sometimes court rules or the preferences of my colleagues trump my choices, but, when I'm free to do so, I adhere to better typographical principles.

I also followed Butterick's advice when I designed the layout of this web site. You'll notice that the blog text is very narrow with wide margins, with large, readable fonts for the headings and body. This was done on purpose. There are some really good blogs with really bad layouts that still use tiny default fonts with text that expands to the edges of the screen. With monitor resolutions now as high as 1440 or even 2160, some blogs are almost unreadable. Butterick helped me to avoid being a casualty of new technology by using classic typographical techniques.

Now, Butterick has updated Typography for Lawyers and I just received an advanced review copy of the second edition (free stuff is the best stuff).

Immediately I noticed a big change between the first and second editions: a new font on the cover! Butterick has actually taken the time to craft his own fonts for use in legal writing, and he used his newest one, Advocate, on the cover. His other fonts, Equity, Concourse, and Triplicate are used throughout the book. To be honest, I'm not crazy about Advocate, but it's perfectly bold and readable and gives the second edition a fresh new look.

There are other changes in the new edition. For example, Butterick has removed some of his punctuation advice (regarding question marks and semicolons) as well as a funny "Note to Argumentative Readers" that graced page 44 of the first edition. But the changes are good - he adds new content and context in other sections to bolster his arguments or clarify his advice.

The most noticeable change was a major overhaul of his list of recommended fonts. He has moved Lyon from being a suggested replacement for Georgia to a suggested replacement for Palatino (which is the font used by the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals in all their decisions). He has also swapped out Starling and Plantin for Tiempos and Verdigris as alternatives to Times New Roman. And speaking of which, he has moved the illuminating "A Brief History of Times New Roman" to a new spot within the font lists, rather than several pages before. It flows better now in its new place and functions as a useful aside.

Two changes are for the worse, however. First, Eldorado no longer makes his list of recommended fonts. Second, Sabon has also been cut, which is an inexcusable mistake that I trust Butterick will rectify in the third edition.

I haven't noticed all the changes from the first to the second edition of Typography for Lawyers, but the changes I've noticed are, for the most part, improvements. Even the changes I don't particularly care for don't really detract from the excellence of the book. The book remains something I will often recommend to other lawyers (and writers in general).

Butterick is here to help. Please, lawyers, fix your barely adequate motions, briefs, and letters and help make the difficult practice of reading the law a little bit more pleasant for everyone.