If you're a proponent of free speech, or, rather, opposed to the government criminalizing speech, the results should be reassuring to you. It seems there is little support for a crackdown by police and other state actors on offensive utterances. America isn't England, after all. We have a tradition of allowing people, by right, to say pretty much anything they want to say no matter how borish or offensive it might be, with few exceptions.

But digging deeper into the poll results reveals something peculiar. "Millennials," those wily scamps aged 18-34, support so-called "hate speech" laws more than anyone else. Forty percent are OK with government restrictions on speech offensive to minority groups. Nobody else comes close. Both Gen X (my generation) and Boomers (my parents) manage less than thirty percent support for such a proposition. It may or may not shock you that the "Silent Generation" (my grandparents) aren't keen on laws against racist commentary at all - eighty percent say no.

The racial breakdown is also not especially surprising. Non-whites support anti-racist speech laws at a rate fifteen points higher than whites. So the two biggest contingents of support come from young people and people of color.

If you run in academic circles or pay attention to the various anti-racist protest movements around the country, you might be inclined to believe that the vast army of non-white PC fascists on college campuses is the force behind this sentiment. But the poll shows that support for hate speech laws declines as college education increases. Granted, there are a LOT more college graduates both older and whiter than the current crop of college protesters fighting for "safe spaces" and racial justice across America's quadrangles, but it still suggests that most support comes from those who haven't graduated high school - though the rank of high school graduates now includes more Millennials than it excludes due to age alone.

No matter which demographic breakdown seems more illuminating, it is important to point out the problems with the underlying premise of outlawing "statements that are offensive to minority groups." How does one determine what is "offensive?" I'm not trying to be obtuse here. There are certain racist things that pretty much everybody can understand to be offensive by their very nature. But if we're going to criminalize certain speech (or, as the poll describes it, let the government "prevent" it), we'll need to define it some way. Who gets to define it?

The answer, of course, is legislators. Leaving aside for a moment the fact that most legislators at all levels across our country are white men, we couldn't outlaw offensive speech unless we had a law defining what counts as offensive. Do we let the police arrest only those who use the "N-word?" Or do we let them arrest someone for saying anything up to and including vaguely troublesome dog whistles like "you people?" Where is the line drawn?

Let's create a hypothetical rule to answer that question. Let's outlaw any explicitly racist slur. The "N-word," of course, but also "Chink," "Wetback," "Negro," and the like. If you use one of those words, in any context, the police can arrest you and you can be charged with a misdemeanor. Also, we'll outlaw any terms or statements that are critical of an entire race as a whole. Anyone who says "black people are animals," or "Hispanics are lazy criminals" or anything broadly nasty such as that can also be arrested and charged.

This rule is passed by a legislature of some sort. Let's call them Congress a decade from now. We've had a couple of elections and we'll presume that a Democratic wave has recaptured both houses. In an effort to appease the liberal base and move the country closer to racial justice, Congress passes the Hate Speech Act that outlaws racist slurs like what we've identified above.

Things go smoothly for a few years. Racist jerks are being arrested and charged and the incidents of public hate speech are on the decline. The law is an effective deterrent for nasty racist commentary. But something else is still happening. Black men are still being killed by police officers at a disproportionate rate. Protesters and angry commentators are still saying and posting things very critical to police forces all over the country.

Then Congress shifts back to the GOP. And, seizing the power of the Hate Speech Act, they amend it to include anything critical of police officers. They call it the Blue Lives Matter Act. Soon, protesters opposed to police brutality get arrested and charged for hate speech by the dozens, and are easily convicted. The law, after all, paints with a wide brush because hate speech can come in varying forms. And why should only racial minorities be protected? Why not police officers, our heroes and protectors?

Such is the danger of criminalizing speech. There is no doubt that racist rhetoric is poisonous to our civil discourse and traumatic to those who are targets of it. Freedom of speech or not, good citizens should not be lobbing hateful comments at each other. Racist slurs and insults reinforce societal inequalities that must be combated and torn down somehow.

But we must resist the urge to "do something" about it if doing something restricts the freedom of expression we enjoy as a right under our Constitution. Not because hateful rhetoric is OK or racists should not be scorned or shunned, but because criminalization of anything increases the power of the police state and gives more power to those who would abuse it. The vague notion that something is "offensive" to someone can be manipulated to benefit the privileged against the oppressed, even if the initial intent was noble.

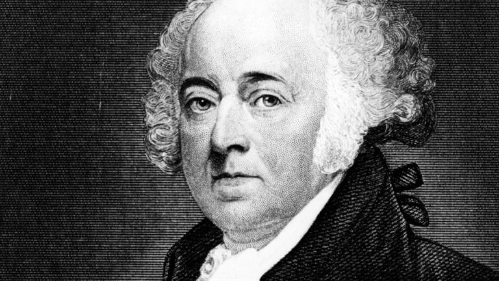

In 1798, in the wake of the French Revolution, President John Adams signed into law the Sedition Act, making it a crime to criticize the national government. Many people (mostly members of Thomas Jefferson's Democratic-Republican Party) were fined and arrested and imprisoned under the law. Though obviously unconstitutional (the First Amendment expressly prohibits Congress from abridging the freedoms of speech and the press), the Supreme Court of 1798 was not the same as it is now. There was no way to have such a law declared unconstitutional. Only after Jefferson became president and the Democratic-Republicans took office was the Sedition Act allowed to expire.

More than a century later, Congress amended the Espionage Act of 1917 to outlaw "disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language" aimed at the U.S. government during World War I. The amendment was known as the Sedition Act of 1918 and was not repealed until 1920, two years after the war ended. It was even upheld as constitutional in the case of Abrams v. United States, 250 U.S. 616 (1919). Violation of the law carried a jail sentence as long as twenty years. The most famous person convicted under the law was Eugene Debs, the socialist labor union organizer and critic of the U.S. government (he spoke out against conscription).

The Sedition Act and its later incarnation as an amendment to the Espionage Act, though draped in the nobility of national security and unity, were tools for those in power to consolidate their control and dominance. And that is the risk posed by any restriction on speech. The people in power need only tweak the definition of what speech is criminalized, then aim the coercive power of the police toward their preferred targets. Perhaps that's not scary if you're the one in power and not the current target of the restriction. But political power can be transitory in this country and your tight hold on government could vanish overnight.

Racist speech is reprehensible and indefensible. Yet criminalizing it would only expand the power of the privileged (who fill the seats of government) and the police (who physically assert their will). Pass a hate speech law against racism today, tomorrow it could easily prohibit the critical speech that fuels effective protest movements against government overreach and police abuse.

As the police batons come cracking down on the heads of outspoken troublemakers merely for uttering the wrong words and they find themselves convicted under laws they once supported, surely some will think to themselves, "but we meant well."