Picking up steam in the wake of Obergefell v. Hodges is the notion that Justice Anthony Kennedy's apparently expansive concept of "dignity" creates problems of application in the law and interference with other rights.

Jonathan Turley writes:

But is it true that Kennedy found a right to marriage based on dignity but not on status? Turley appears to argue that Kennedy's reasoning includes no equal protection aspect at all, that how we define dignity - and how we subsequently protect it - has nothing to do with the identity of the person seeking it. I'm not convinced.

I'm not convinced because Justice Kennedy wrote a lot more than just the word "dignity" in Obergefell. If you read what he actually wrote, you can see that he invokes dignity in very specific ways that involve both limited situations and identifiable groups of people.

Justice Kennedy invokes dignity for the first time in Obergefell on page 3, in a discussion of history:

Marriage promises dignity to men and women without regard to their station in life. This is the language of equal protection. Marriage promises dignity no matter who you are. Kennedy is making a key point here: we already extend dignity to different-sex couples. He's not creating a right to dignity, he's identifying one that already exists but is being denied to a specific group.

Justice Kennedy's next invocation of "dignity" comes on page 6:

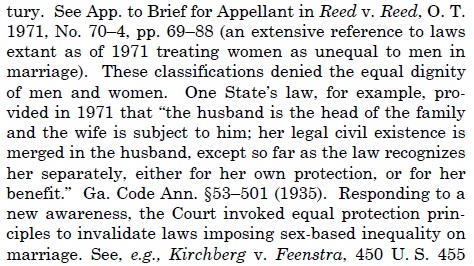

Again, the invocation of dignity is within the confines of equal protection. Men already enjoyed dignity in marriage. It was denied to women. But women, as a group, also have a right to dignity that the law cannot strip on the basis of their sex.

On the next page, Justice Kennedy turns to the history of gay and lesbian discrimination. Again, he defines dignity through an equal protection lens:

He speaks of the dignity of homosexuals "in their own distinct identity," not a nebulous concept of dignity that floats in space to be claimed by anyone who drifts by.

So Justice Kennedy's concept of dignity and its history is intertwined with equal protection: dignity is a right that has regularly been denied to discrete groups of people based on who they are.

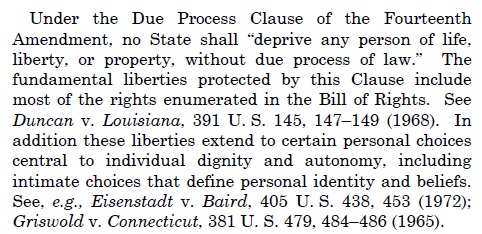

Dignity is also situational. Justice Kennedy confines his definition to a narrow set of decisions that, again, are intertwined with the concept of equal protection:

Read carefully the second sentence. The concept of dignity applies to "intimate choices that define personal identity and beliefs." First, this language is not really broad, especially considering the cases to which Kennedy cites. Eisenstadt and Griswold were reproductive freedom cases, which declared that married and unmarried people have a right to make contraceptive decisions for themselves without interference by the government. Kennedy similarly defined dignity in this narrow way in Lawrence v. Texas, which found a dignity right in private, consensual sexual relations. So this dangerous slippery slope of dignity has only really been found in sex and marriage.

Second, the choices encompassed in the dignity right "define personal identity." This is equal protection language again. And there's more:

As Kennedy is sure to say, his identification of a dignity right "is true for all persons, whatever their sexual orientation." The gay marriage bans challenged in Obergefell interfered with a specific group's fundamental right to marry, which infringed "their autonomy to make such profound choices."

Near the end of his opinion, Kennedy engages in a discussion of equal protection that has frustrated commentators (and the Court's dissenters) because it appears cursory. The Supreme Court has established extensive doctrine to identify and scrutinize equal protection violations, but Kennedy's opinion barely addresses any of it. Instead, he talks in broad, historical terms, about how marriage has changed over time to include more people and more autonomy.

This passage shows once again that Kennedy's concept of dignity requires equality of application:

Coverture laws denied "equal dignity," not just "dignity" in general. Marriage laws, historically, protected the dignity of men to make intimate decisions for themselves about who to create a family with. But they denied that freedom to women, who became property in marriage. Like all the other places Justice Kennedy invokes dignity in Obergefell, this concept cannot exist independently of the rights of others. One person's dignity creates a baseline for the dignity of others - where one person has freedom to make intimate choices, those intimate choices cannot be denied to someone else based on their identity.

Kennedy's final use of the word "dignity" appears in his soaring final paragraph:

The phrase "equal dignity" is critical to Kennedy's concept of the right. The law already protects the dignity of different-sex couples to make the intimate and personal choice to marry, a right that has long been considered fundamental. The law must also protect the dignity of same-sex couples to exercise this right.

Jonathan Turley says "it is not clear what a right to dignity portends," and then offers some rhetorical questions:

First, it is not "clearly undignified" to be denied a wedding cake. Kennedy's concept of dignity, as he has spelled it out in his opinions, does not extend to being served by a business. And it also doesn't extend to feelings of indignity by a business owner having to serve someone they find objectionable. Dignity includes having consensual sex, having (or not having) children, and marriage. That's about it. Those are the key situations involved in all of Kennedy's opinions that invoke a right to dignity. They all involve intimacy and the creation of a personal identity as a partner, spouse, and parent.

Regulations of business, such as public accommodation anti-discrimination laws, have long been held to be constitutional without regard to "dignity." First of all, businesses are voluntary enterprises. And though decisions about sex and marriage are also voluntary, the operation of a business does not seem like it would qualify as the kind of intimacy that Justice Kennedy's opinions seek to protect.

Second, Justice Kennedy's concern for dignity arises where it has been categorically denied to a group of people based solely on their identity. This "dignity" does not exist independently from equal protection. Do anti-discrimination laws deny the dignity of bigoted business owners as a group? How would you classify this group? By their discriminatory actions alone?* Which ones? Anti-discrimination laws certainly don't single out anyone. You can't argue that anti-discrimination laws single out Christians, because (1) the laws apply to everyone equally, and (2) lots of Christians don't discriminate and many argue that their faith actually prohibits it. So whose dignity do such laws infringe?

It is interesting that affirming a right to equal dignity and autonomy within the very narrow confines of intimate, family decisions could lead observers to propose yet another parade of horribles, especially astute observers such as Jonathan Turley. That's Justice Scalia's job. A fair reading of Kennedy's "dignity" opinions - Lawrence, Windsor, and Obergefell - shows that he does not propose an expansive, nebulous right to dignity, but a narrow right to key personal decisions which require the equal protection of the law. Calm down, Chicken Littles.

*Consider that Lawrence overruled Bowers v. Hardwick, which defined homosexuality not as an orientation, but as voluntary actions. So the idea that a classification can turn solely on behavior is already questionable.